Introduction

In 2004, as part of my graduate dissertation, I examined Kenya’s emerging youth bulge and its socio-economic implications. At the time, the data was both compelling and sobering: the 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) revealed a population structure heavily skewed toward young people, with a rapidly growing cohort under 25. We stood at the threshold of a demographic shift whose trajectory could either elevate or destabilize the nation.

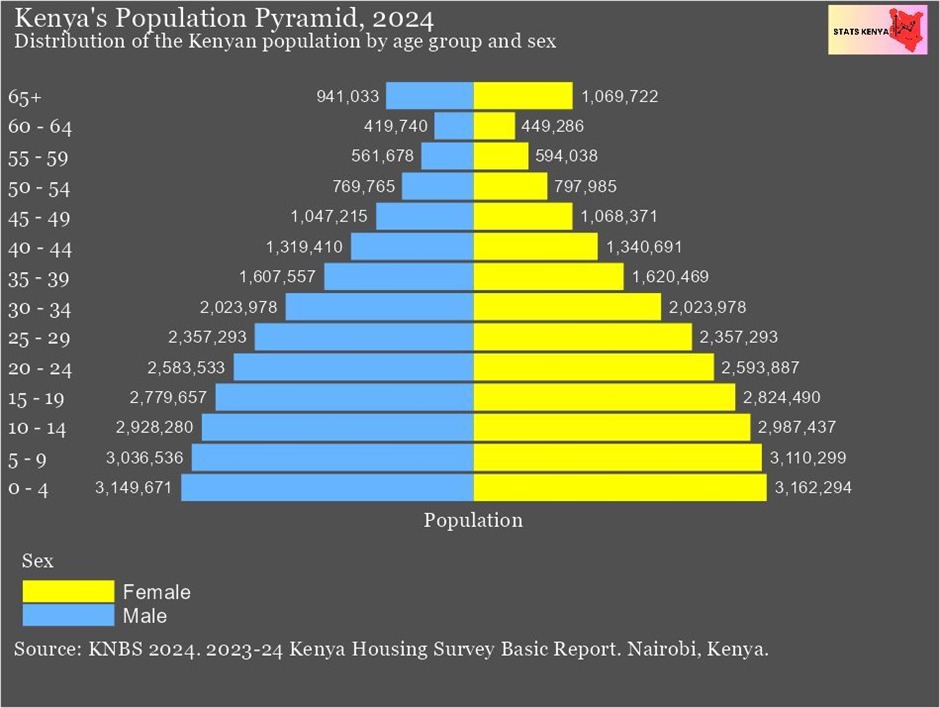

Two decades on, the demographic fundamentals remain largely unchanged, if anything, they have deepened. The recently released 2023/24 Kenya Housing Survey Report confirms what we suspected then: the youth bulge has matured, but Kenya has not sufficiently pivoted to leverage it.

Today, Kenya’s population approaches 55 million, with over 75% under the age of 35. This demographic is both an unparalleled resource and a ticking clock: without effective integration into the economy, social and political stability will be strained.

The 2023 Sessional Paper on Kenya’s National Population Policy underscores the stakes: rapid population growth, high dependency ratios, and uneven socio-economic outcomes across regions. Youth unemployment remains stubbornly high. Informality dominates labor markets. The window for harnessing a demographic dividend is still open – but it is narrowing.

What can we learn from this two-decade journey?

Here are three major lessons from Kenya’s experience with the youth bulge:

- Demography is Not Destiny — Policy Choices Matter

The KDHS 2003 clearly laid out Kenya’s youthful age structure – a time-limited opportunity for transformation. Comparative research showed that East Asian economies such as South Korea and Vietnam turned similar bulges into dividends by investing in health, education, and employment creation.

Kenya’s own journey has been mixed. We expanded access to education, notably through Free Primary Education (2003) and Free Day Secondary Education (2008) and achieved a rise in the working-age population from 54% in 2009 to 57% in 2019. Yet the alignment between education and labor market needs remains weak, particularly in technical and vocational training. Fertility rates have declined nationally, from 8.1 children per woman in the late 1970s to 3.4 in 2019, but remain high in some counties, perpetuating regional inequalities.

The 2023/24 Housing Survey points to persistent housing insecurity among youth-headed households and inadequate transition from schooling to formal work. It is a reminder that demographics only become dividends when backed by long-term, inclusive planning.

“A youth-heavy population is a powerful resource—but only if matched with opportunity.”

Countries that reap the demographic dividend—like South Korea or Vietnam—do so not just because they have youth, but because they plan and invest strategically. Kenya still has a window, but it’s closing fast.

- Jobs Are the Currency of Demographic Stability

In 2004, youth unemployment was already a growing concern, and warnings were raised about the political and social consequences of a generation sidelined from the economy. Two decades later, much of that concern has materialized. By 2019, the unemployment rate stood at about 12%, with nearly 68% of the unemployed below the age of 35.

Recent World Bank data and the 2023/24 Kenya Housing Survey confirm that youth remain disproportionately affected by joblessness, underemployment, and informal work. Even among those with tertiary qualifications, few secure stable employment. Many turn to gig work, small-scale retail, or remain dependent on family support. Labor underutilization is highest among 20–24-year-olds (27.1%), and the NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) rate for this age group stands at 24%.

This is not merely an economic challenge — it is a social stability risk. High rates of economic exclusion limit growth, fuel disillusionment, and increase the risk of migration pressures, crime, and political unrest.

“You cannot build a stable society on frustrated potential.”

The Housing Survey further reveals that youth are the least likely to own or rent stable housing, a direct reflection of income insecurity. Without large-scale, youth-friendly job creation, particularly in agriculture, digital services, the green economy, and SME sectors, Kenya’s youth bulge will strain social systems instead of fueling sustainable growth.

- Youth Inclusion Must Be Designed, Not Assumed

Over the past two decades, Kenya has made commendable progress in youth policy – establishing the Youth Enterprise Development Fund (2006), the Uwezo Fund (2013), and the Kenya Youth Development Policy (2019). Devolution has enabled county-level youth programs, and more young leaders are being elected into public office. However, many of these gains remain tokenistic or underfunded, with weak implementation and limited reach.

The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2003 hinted at early signs of youth disengagement. Two decades later, that disengagement is clearer: voter turnout among 18–35-year-olds in the 2022 elections was significantly lower than in older age groups; mental health concerns, particularly depression and anxiety, are on the rise; and surveys show growing distrust in political institutions.

The Sessional Paper No. 1 of 2023 emphasizes that youth are not just “future leaders” — they are present actors whose inclusion in policy design, budgeting, and governance is essential for national stability and development. Excluding them risks not only policy failure but also civic backlash, as excluded groups either opt out of participation or mobilize in opposition.

Urbanization trends add urgency to this agenda. Kenya’s urban population has risen from 19.3% in 1999 to over 31% in 2019, with young people making up the majority of internal migrants. Many end up in informal settlements, facing overcrowding, unemployment, and limited access to services. The 2024 Kenya Housing Survey found that youth-headed households have the lowest rates of home ownership and secure rental tenure in the country, a tangible indicator of economic and social marginalization.

Both the Housing Survey and the Sessional Paper call for targeted, structural reforms to promote inclusion. This includes:

- Inclusive urban planning that integrates affordable housing, transport, and green spaces in youth-dense areas.

- Expansion of digital infrastructure, particularly in underserved counties, to unlock access to remote jobs, e-services, and civic engagement platforms.

- Participatory governance mechanisms, such as county youth assemblies and national consultative forums, to institutionalize youth voice in decision-making.

These are not luxuries. They are foundations for dignity, productivity, and civic engagement, and essential safeguards against deepening alienation among Kenya’s largest demographic group.

Broader Context: Population Dynamics and Policy Gaps

Kenya’s demographic reality is shaped by three interlinked forces:

- Fertility. While national Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is declining, regional disparities persist. Counties such as Mandera and Wajir still record fertility rates above 5.0. High adolescent fertility (over 80 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19) sustains the youth bulge and strains education and health systems.

- Mortality. Life expectancy has improved, and the elderly (60+) are the fastest-growing segment (up 42% from 2009–2019). Yet maternal mortality remains high (355 per 100,000 live births in 2019) and urban health disparities are widening.

- Migration and Urbanization. Rural-to-urban migration is accelerating; urbanization rose from 19.3% in 1999 to over 31% in 2019. While cities concentrate opportunity, they also face overcrowding, informal settlements, and rising living costs.

These demographic shifts amplify the urgency of aligning education, labor, housing, and health policies with the realities of a youthful, mobile, and increasingly urban population.

Conclusion: Turning Reflection into Renewal

Two decades after the KDHS 2003 and my own dissertation warning, Kenya remains at a demographic crossroads. The youth bulge could yet yield a dividend — or it could deepen inequality and instability.

The future is not predetermined. By shifting from fragmented programs to deliberate, sustained investment in jobs, skills, and inclusion, we can still secure the promise of our youthful nation.

The question is no longer whether Kenya has a youth bulge. The question is whether we are ready to build around it, believe in it, and benefit from it.

Bibliography

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2023/24 Kenya Housing Survey Report. Nairobi: KNBS, 2024.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2003 & 2022. Nairobi: KNBS, various years.

- National Council for Population and Development (NCPD). Sessional Paper No. 1 of 2023 on Kenya National Population Policy for Sustainable Development. Nairobi: NCPD, 2024.

- Okumu, T. O. “Assessing the Impact of Population Dynamics in Kenya: A Need for Policy Implementation.” Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth Science International 28(2): 53–69, 2024.

- World Bank. Kenya Economic Update: From Recovery to Better Jobs. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2023.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Kenya Population Situation Analysis. Nairobi: UNFPA, 2022.

- African Union Commission. AU Demographic Dividend Roadmap. Addis Ababa: AUC, 2017.

No responses yet